Did Theodore Roosevelt ever consider divorce? Divorce is something rarely associated with Theodore Roosevelt anymore yet something that certainly concerned him. He was a committed husband and loving family man, and so his consideration of divorce was not paired with his own marriage, but rather with its implications on society at large. During the turn of the century Roosevelt noticed the slow-changing cultural views of both marriage and divorce, and he saw it as a threat to society.

Theodore Roosevelt Engrossed in a Book (Per Usual)

President Theodore Roosevelt was so engrossed in Robert Grant’s novel, the romantic drama, The Undercurrent, that he wrote Grant about its characters saying, “If Constance does not marry Gordon my relationship with you will be seriously strained.” A few months later, after finishing the book, Roosevelt, with great emotional investment, wrote to Grant again: “Constance turned out like a brick and everything ended exactly as it ought to.” This was not the only time Roosevelt was completely entangled in one of Grant’s books. When reading another, Unleavened Bread, Roosevelt said, “I became so absorbed in it that I could not put it down until I finished it.” It wasn’t just the writing style itself or the storytelling that interested Roosevelt, but the themes and questions Grant evoked through his stories about divorce.

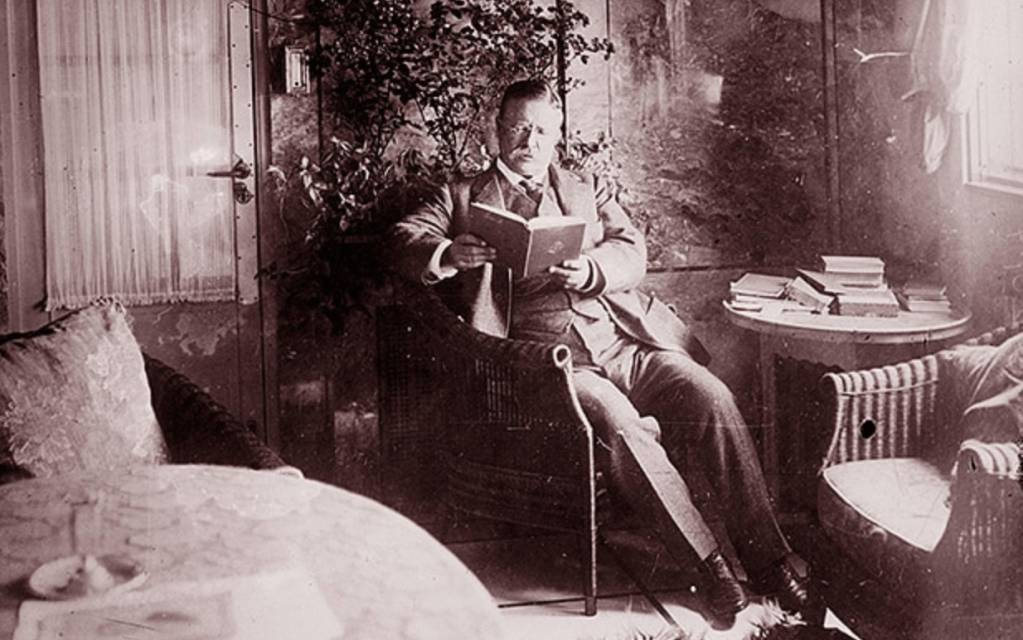

Theodore Roosevelt and Author Robert Grant

Among the many authors and poets with whom Theodore Roosevelt maintained a relationship, this is one who stands apart from the rest for the most extensive paper trail of letters. Robert Grant was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1852. He was a graduate of Harvard University and lived the rest of his life in Boston as a novelist and probate court judge. He met Theodore Roosevelt briefly when he was at law school, but really got to know him on a ocean voyage from New York to England. The grief-stricken young Roosevelt, who had just recently lost his wife and mother to death, was working on his first book, The Naval War of 1812. During their sea travel the two engaged in conversation and became reacquainted. Grant wrote, “there was fog and a menace of icebergs,” and he wrote that Roosevelt, while looking out the window of the boat at the ominous sea, expressed that “except for a wish to finish his history of our naval war of 1812, he would not care if he was lost at sea.”

These cold days at sea were the beginning of a lasting friendship and Roosevelt’s interest in Grant’s writings, to which he expressed a particular fondness. In one letter Roosevelt praised Grant’s work, telling him he had “done real good in this country.” He wrote, “The first requisite for a book of any kind, must be that it’s interesting; and the things that are interesting must have the further quality of being useful. It is not every man, however, who can serve the double purpose; who can double arouse interest and give pleasure on the one hand, and on the other can make himself felt as one of the forces that tell for strength and decency in national life. It has been your good fortune to achieve success in both these ways.”

An Invitation to the White House

During the election of 1904 Roosevelt wrote to Grant: “When the election is over I want to have a chance of seeing you, not just for ten or fifteen minutes, but when I can go over at length with you some of the problems you touch upon in The Undercurrent.” Later, in December of 1904 Roosevelt wrote Grant inviting him and his wife to attend the judiciary dinner at the White House, spend the night, and stay through lunch the next day. On more than one occasion Roosevelt wrote in letters how he wanted to discuss matters in Grant’s books with him. One of the themes most explored by the two was divorce which was the main theme in Grant’s novel, The Undercurrent. Both men were drawn to divorce’s effects on society and the legality and morality behind it. A term both men brought up in their correspondence was “easy divorce.”

Easy Divorce

In the 19th century marriage was oftentimes a vehicle to gain property rights, move social classes, and establish a family. It was a choice and a commitment but oftentimes seen through a pragmatic lens of what works best for building a family. By the early 1900s, pragmatism in the matter was losing its edge, and a greater emphasis was put on romance as being the main reason to wed and lack of it a reason for divorce. Throughout the 1800s the divorce rate had increased three-fold. By 1880 there was one divorce for every 21 marriages; in 1900 there was one divorce for every twelve marriages. This was becoming a growing societal concern at the time and the subject of many editorials, sermons, and even government investigations. What Roosevelt and Grant referred to as “easy divorce” had a two -fold meaning. In one regard, as Grant explained in his writing, occurred when spouses were simply tired or bored of each other and would approach divorce flippantly. Roosevelt saw this particularly concerning among the wealthiest of Americans. He wrote, “It has been shocking to me to hear young girls about to get married calmly speculating how long it will be before they get a divorce.”

In another regard, “easy divorce” referred to the ease with which a couple could divorce in certain states. Roosevelt wrote, “‘There is a wide-spread conviction that the divorce laws are dangerously lax and indifferently administered in some of the States, resulting in a diminishing regard for the sanctity of the marriage relation.” He expressed that the effect of easy divorce had been “very bad” and that he did “unqualifiedly condemn” it. In certain states where divorce was not as “easily” achieved without fault or cause, some of the wealthiest and sly Americans achieved the staging of affairs. A man, or even the agreeing couple, wishing for a divorce, at the cost of his reputation, would hire a mistress and a photographer to provide “evidence” of adultery in a court of law to legalize a divorce.

The Sanctity of Marriage

As an upright family man and husband, Roosevelt wrote extensively about family life and the role of man and woman in marriage. His view of marriage was influenced heavily by his Christian faith. He wrote, “A man must think well before he marries. He must be a tender and considerate husband and realize that there is no other human being to whom he owes so much of love and regard and consideration as he does to the woman who with pain bears and with labor rears the children that are his.”

In an address to the Inter-Church Conference he said, “Questions like the tariff and the currency are of literally no consequence whatsoever compared with the vital question of having the unit of our social life, the home, preserved. It is impossible to overstate the importance of the cause you represent. If the average husband and wife fulfill their duties toward one another and toward their children as Christianity teaches them, then we may rest absolutely assured that the other problems will solve themselves. But if we have solved every other problem in the wisest possible way it shall profit us nothing if we have lost our own national soul, and we will have lost it if we do not have the question of the relations of the family put upon the proper basis.” He called family “the very foundation of our social organization” and saw the threat of “easy divorce” upon it. In one particular case of divorce, he called it “the worst form of anarchy.”

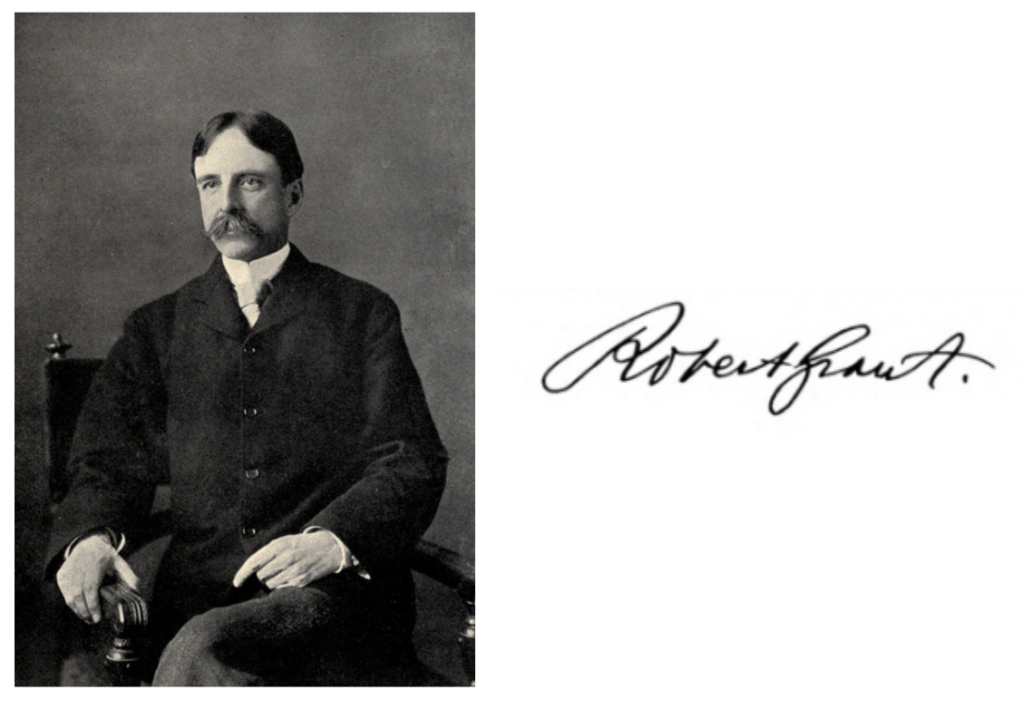

The Threat of Socialism

Roosevelt was also ahead of his time, assessing the threat in America of growing socialism and Marxism, which hold as a tenant the deconstruction of the nuclear family. In his critique of socialism in his book, The Foes in Our Own Household, he addressed the socialist vision to abolish the institution of marriage and regulate child bearing at the governmental level, creating a “nation of fatherless children” and simple subjects of the state. Roosevelt warned that the socialist movement was an “attack on marriage and family,” and wrote, “When home ties are loosened, when men and women cease to regard a worthy family life, with all its duties fully performed, and all its responsibilities lived up as the best life worth living, then evil days for the (nation) are at hand.” Roosevelt saw the sanctity of marriage and family as the building blocks of society and perhaps saw “easy divorce” as one of the first dominos to fall in this chain leading to the degradation of family and the nation at large. This led him to call for the authorization of the Director of the Census to collect and publish data on divorce rates and push for the National Congress on Uniform Divorce Laws in 1906.

Shaping the Culture

Reading and social change at many times went together for Roosevelt. Although Roosevelt certainly did read for pleasure, Roosevelt’s interest and involvement in the literary world also was a means of facilitating the direction of national culture and identity. Roosevelt lifted up authors and poets who embraced traditional Judeo-Christian values and benefited the morale and moral character of the nation. He sought these writers out and often helped propel their careers through great encouragement, review, and also connecting them with publishers. In the 21st century we see how influential the entertainment media is on the life and culture of the nation. The novelists and poets of the 19th and early 20th century were the closest equivalent to the entertainment media and celebrity influence we have today. If Roosevelt could engage the writers of the time and press his influence on them, he would steer the direction of culture and the nation.

Roosevelt in his autobiography famously quoted, “Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.” In terms of influencing national culture, he was certainly doing this through his propping up of fellow authors, giving lengthy speeches on moral character, and writing his own books on moral topics: “Realizable Ideals”, “The Strenuous Life”, and “American Ideals.” With the cultural and moral concern at hand, and acknowledging the threat of socialism on the fabric of the nation, it is clear to see how “easy divorce” was a topic of great interest to Roosevelt. How did divorce fit in with American values? To what extent was it permissible? The legal aspects of divorce in Grant’s work were therefore of particular interest to Roosevelt as they brought to the forefront these questions.

The Poetry of Robert Grant

Robert Grant regularly dealt with divorce as a probate judge, and although he used the theme of divorce in a few of his novels, he had explored other themes as well. He had written sixteen novels, a play, and an autobiography. Though he is not largely recognized as a poet, he did write a number of poems as well which appeared sparingly in different periodicals including Harper’s Weekly, Scribner’s Magazine, Metropolitan Magazine, as well as delivered at Harvard class reunions over a span of many years.

In 1926 he compiled a collection of his previously published and shared poems in a book he had privately printed called, Occasional Verses. He had only three hundred copies of the book printed and gave them as Christmas presents to family and friends. Among the known recipients are Howard Taft’s son, Henry W. Taft and Theodore Roosevelt’s sister, Corinne Roosevelt Robinson. Touched by the gesture and the years of friendship, Corinne Robinson penned a poem in dedication to Grant published in her book Out of Nymph. In it she illustrates the joy and fond memories she had of discussing poetry with Grant and her brother. She inscribed Grant’s copy: “For Judge Robert Grant, my old friend, my brother Theodore Roosevelt’s old friend with happy memories…” She concluded her poem with, “Thank you old friend, for to you I am beholden;— God bless that wakes memories golden!”

Robert Grant offered a lasting friendship of joy and literary works of good humor but also stories of weightier matters which spurred Roosevelt on in his concerns about “easy divorce” in the nation. Below are two poems from Grant, one concerning the love for his wife, written for her on the occasion of their 25th anniversary in 1908 and another dealing with divorce as a probate judge, delivered at a dinner of the Bar Association of the County of Middlesex, Dec. 4, 1907. These poems are made available through Henry W. Taft’s original copy of Grant’s Book, Occasional Verses, pictured below:

If you enjoyed this piece you may enjoy reading more about Roosevelt’s values and ideals in his book Realizable Ideals and the Key to Success in Life or my book Theodore Roosevelt for the Holidays: Christmas and Thanksgiving with the Bull Moose.